Our Favorite Fall Hikes for Leaf Peeping

Autumn is here and, as anyone who delights in the season knows, it’s prime time for leaf peeping! If you enjoy a good fall hike, the Finger Lakes region has many locations that feature sun-dappled hills emblazoned with brilliant fall colors. Even better, this selection includes options for longer or shorter hikes and opportunities for viewing waterfalls, lakes, and a mighty river. Put on a sweater and experience fall’s radiant beauty at these locations chosen by the staff at the Finger Lakes Land Trust.

Clark Reservation State Park

At this 377-acre park in Onondaga County, you can follow the rugged Cliff Trail for stunning views of Glacier Lake, formed during the last ice age. In autumn, the orange, yellow, and red fall foliage provides a stark contrast, and the lake is easily seen and provides a stunning photo op. Other trails wind through deep forest and beside the lake’s outlet/swamp so there are multiple routes through a variety of niches.

Fillmore Glen State Park

Located in the village of Moravia, Fillmore Glen features a deep gorge with stunning waterfalls and over seven miles of trails including the north rim, the south rim, and the real gem — the gorge trail. Autumn is a notably beautiful time to visit, either when the leaves are emblazoned with contrasting colors or just after fallen leaves reveal parts of the gorge previously hidden from view by the dense understory.

Harriet Hollister Spencer Recreation Area

Located in the high hills between Honeoye and Hemlock Lakes, Harriet Hollister boasts a roughly 20-mile trail network that weaves through mostly deciduous forest. Visitors can enjoy a deep woodland feel with broad stable trails that include lots of lengthy lines-of-sight. Not to mention the picturesque panoramic view of Honeoye Lake and its steep-sided valley along the Overlook Trail.

Labrador Hollow Unique Area

The most popular destination in Labrador Hollow is the universally accessible, quarter-mile path to Tinker Falls. Tinker Falls is a stunning example of a “hanging” falls. Its origin dates back to when New York and much of the North American continent was part of an inland sea. Second in popularity, and perhaps also in scenery, is the climb to the Jones Hill hang glider launch. From this vantage point, you can look down upon the hollow and Labrador Pond, at one of the few truly scenic hilltop vistas available along trails in the Finger Lakes region.

Lick Brook Gorge

Pull on your hiking boots and follow the trails in this forest, along the rim of Lick Brook gorge, where multiple waterfalls splash down on their way to Cayuga Lake. The Sweedler and Thayer Preserves, owned by the Finger Lakes Land Trust, provide excellent examples of the area’s geologic history and ecological systems. Different species of oak and maple can be found, as well as the less common cucumber magnolia and mountain maple. In autumn, Lick Brook becomes part of the colorful tapestry that spreads across the region in red, yellow, and orange.

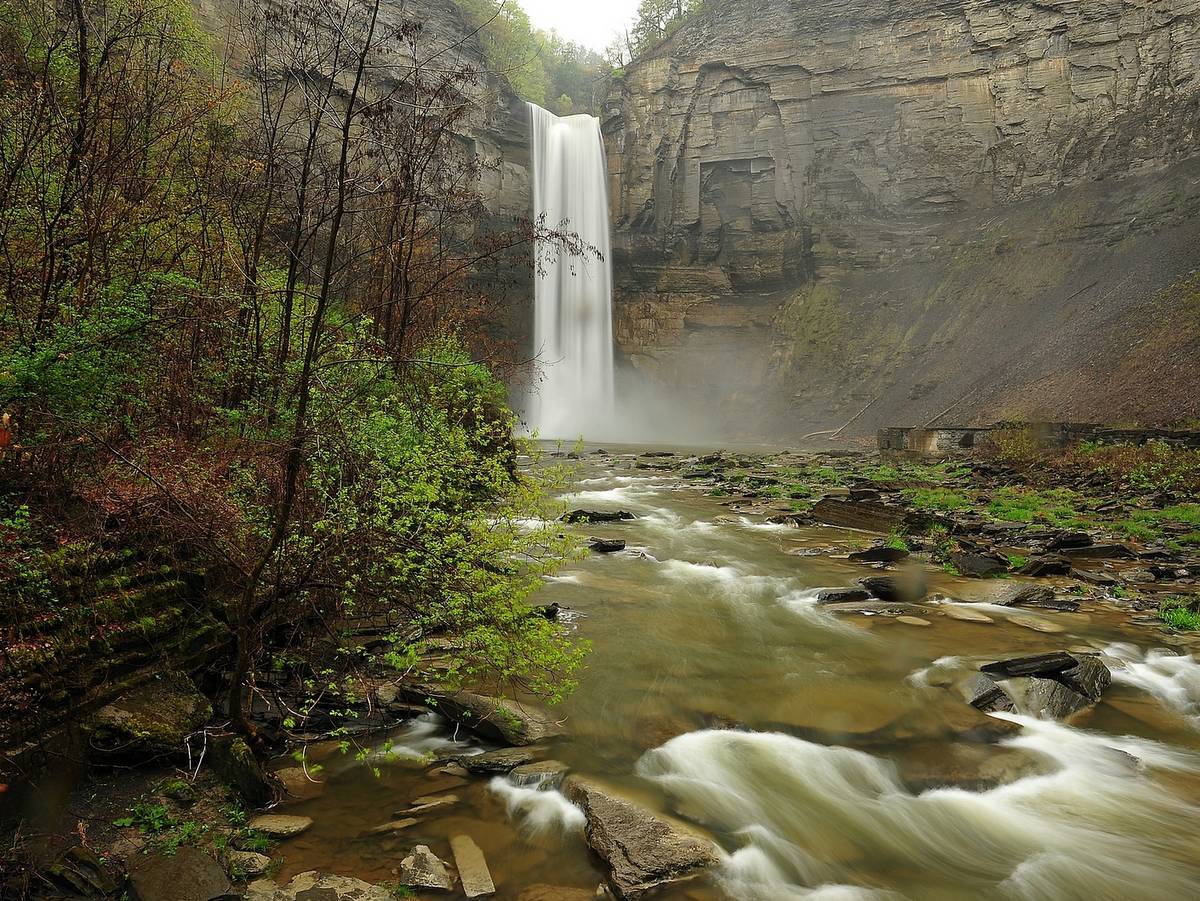

Letchworth State Park

Letchworth and its rich history encompass seventeen miles of staggeringly sheer gorge, three towering and broad waterfalls, dozens of smaller waterfalls, 66 miles of trails, an abundance of overnight options, and opportunities to explore the park via foot, bike, horse, raft or even hot-air balloon! There is a greater quantity of trails on the western side of the gorge, with most branching off from and paralleling the main Park Road. Most lead to scenic overlooks with panoramic views of the gorge and Genesee River.

Steege Hill Nature Preserve

At the Finger Lakes Land Trust’s 793-acre Steege Hill Nature Preserve in Big Flats, there are seven miles of trails that weave through a predominantly oak and hickory forest. The largest of the Land Trust’s conservation areas, Steege Hill rests high above the Chemung River and offers ample solitude for hikers who wish to avoid crowds.